Special Research on the Titanium Industry (Part I): The Origin, Applications, and Current Status of the “Universal Metal” (Part 1)

Special Research on the Titanium Industry (Part I): The Origin, Applications, and Current Status of the “Universal Metal” (Part 1)

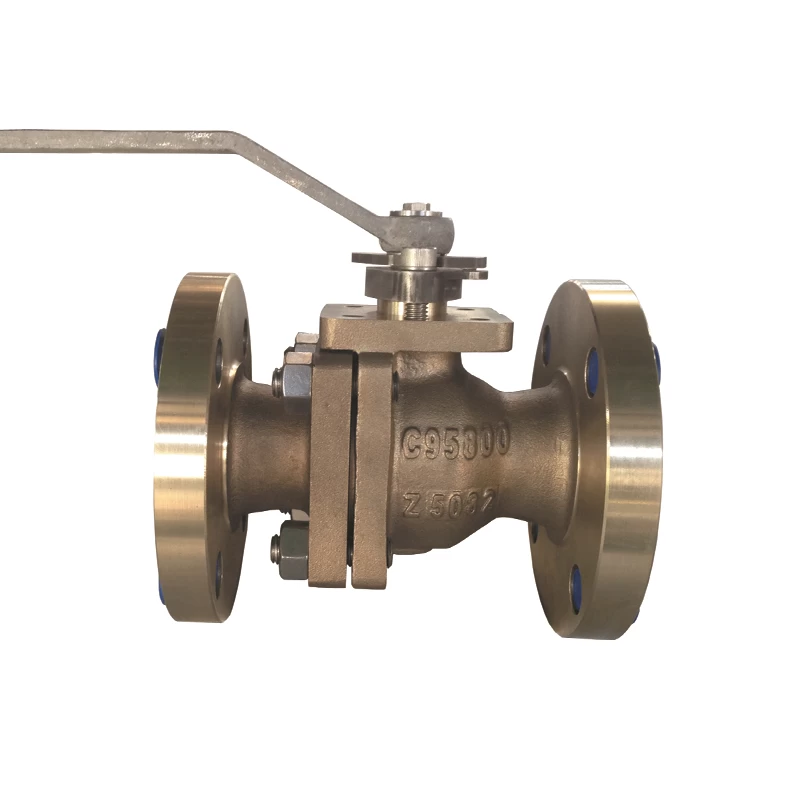

Titanium, with the chemical symbol Ti, is the 22nd element in the periodic table. Commonly associated with aerospace and other high-end sectors, titanium is often seen as a “premium” metal. However, it has already penetrated deeply into our everyday lives: from the toothpaste you use daily—likely containing titanium dioxide as a whitening agent—to the bedroom walls painted with titanium-based pigments, and the titanium alloy eyeglass frames you wear. As a titanium gate valve manufacturer or user of titanium-based products, one quickly comes to appreciate its widespread relevance and high-performance benefits across various industries.

Due to its excellent resistance to high and low temperatures, strong acids and alkalis, as well as its high strength and low density, titanium and its alloys are recognized as ideal substitutes for steel, stainless steel, copper and its alloys, lead, nickel, zinc, graphite, and stone materials. Its application scope is continually expanding. Thus, titanium is honored as the “universal metal” in the kingdom of metallic materials, and is seen as the "third metal" after iron and aluminum, as well as a strategic and aerospace-critical material.

Yet, because titanium cannot be found in pure metallic form in nature and is difficult to extract, its discovery and industrial application took a long path. Although British clergyman W. Gregor discovered titanium in ilmenite as early as 1791, it wasn’t until 1795 that German chemist M.H. Klaproth confirmed its existence during the study of rutile and named it after the Greek mythological Titans.

After over a century of exploration, American scientist M.A. Hunter successfully extracted pure titanium using sodium reduction of TiCl₄ in 1910. In 1940, Luxembourgish scientist W.J. Kroll developed the magnesium reduction method, known today as the Kroll process. In 1948, the U.S. produced 2 tons of sponge titanium using this method, marking the start of titanium's industrial-scale production.

Characteristics of Titanium Metal

Titanium exhibits a high strength-to-weight ratio. Although titanium alloys are slightly less strong than some traditional steels, their much lower density gives them superior specific strength. This makes them ideal for aerospace industries where lightweight and high-strength materials are in demand.

Titanium also offers outstanding corrosion resistance, which is crucial as corrosion is a common cause of industrial equipment failure. Despite being a reactive element, titanium alloys form a dense oxide layer on their surfaces, which effectively isolates the metal from corrosive environments. This passive layer can self-heal rapidly if damaged, maintaining its protection up to temperatures of around 315°C.

Furthermore, titanium is non-magnetic, non-toxic, and highly biocompatible. As titanium is a trace element in the human body and exhibits strong compatibility with tissues and blood, it is widely used in the medical field.

Titanium alloys also operate across a wide temperature range. Certain alloys can perform long-term at temperatures exceeding 600°C. Low-temperature titanium alloys, such as TA7 and TC4, become stronger as the temperature drops while maintaining good ductility and toughness down to -196°C to -253°C, making them ideal for cryogenic tanks and storage containers.

Product Types and Applications

Currently, titanium products are mainly categorized into three groups: titanium dioxide (TiO₂), sponge titanium, and titanium processed materials. Other products include titanium ingots, titanium powder, and titanium equipment. These are used across aerospace, industrial, and civilian sectors.

Titanium dioxide is a white pigment mainly used in coatings, plastics, inks, and paper.

Sponge titanium serves as the raw material for further processing and is usually light gray in appearance.

Titanium processed materials are made by melting sponge titanium into ingots and further shaping them through forging, rolling, or extrusion into plates, bars, pipes, and castings.

+86 512 68781993

+86 512 68781993