Boiler Terminology Explanation (Part 9)

Boiler Terminology Explanation (Part 9)

83. Quenching (hardening: quenching) is a heat treatment process in which steel is heated to the austenitizing temperature, held for a certain period, and then cooled at a rate greater than the critical cooling rate to obtain non-diffusive transformation structures such as martensite, bainite, and austenite. This process is commonly known as hardening. The primary purpose is to increase the strength and hardness of the steel. The quenching process involves three key aspects: selecting the quenching temperature, determining the heating time, and choosing the cooling medium. The requirement is to achieve the desired mechanical properties while minimizing deformation and preventing cracking.

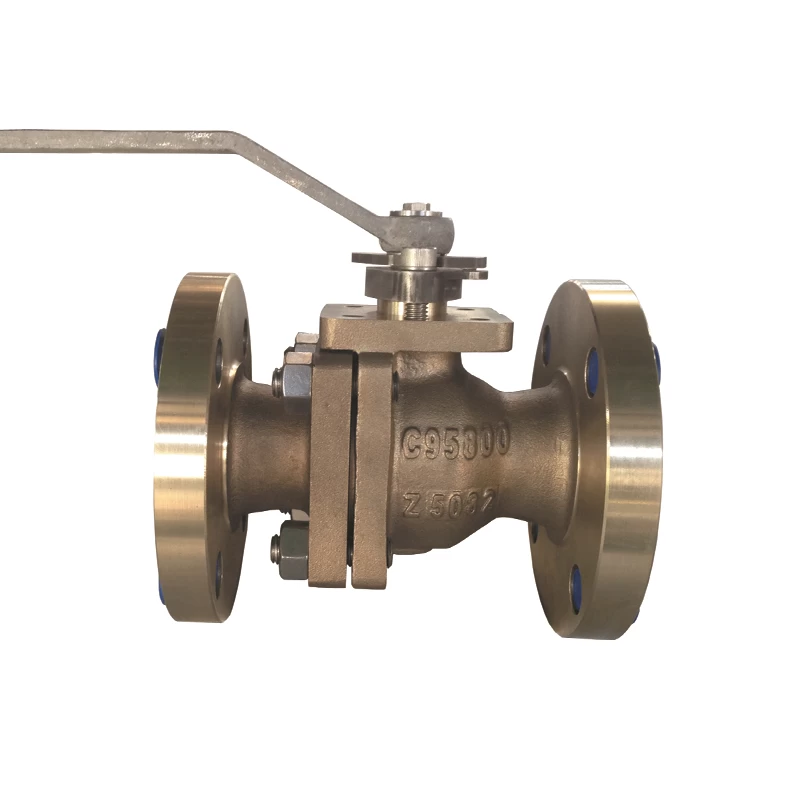

For example, in the China C63200 check valve factory, selecting the appropriate quenching process ensures the check valve components achieve the necessary hardness and durability to withstand demanding operational conditions.

84. Tempering (tempering) is a heat treatment process in which quenched steel is reheated to a certain temperature, held for a period, and then cooled. The main purposes of tempering are: (1) to eliminate the brittleness and internal stresses in the steel after quenching, (2) to control the precipitation of martensite and the aggregation of carbides by adjusting tempering parameters to regulate hardness, (3) to stabilize the microstructure by transforming unstable martensite and retained austenite into a more stable phase, and (4) in highly hardenable alloy steels, to soften the material using air quenching combined with high-temperature tempering, achieving better results than annealing.

85. Corrosion (corrosion) refers to the deterioration and destruction of metals due to chemical, electrochemical reactions, and physical interactions with the surrounding environment. Chemical corrosion occurs when the material or equipment surface reacts directly with the surrounding medium, leading to metal degradation, commonly in gaseous environments. Corrosion involving electric current generation is classified as electrochemical corrosion.

86. Uniform corrosion occurs when a material or equipment surface undergoes widespread chemical or electrochemical reactions with the surrounding medium. Although uniform corrosion does not significantly shorten the service life of equipment, large-scale metal corrosion can produce corrosion byproducts. If these byproducts enter the boiler and accumulate on pipe walls, they can lead to under-deposit corrosion and other damage.

87. Galvanic corrosion occurs when two metals with different potentials come into contact (or are connected via a conductor) in the presence of an electrolyte solution. This phenomenon is also known as dissimilar metal corrosion. An example is the corrosion that occurs at the expansion joint between a copper alloy condenser tube and a copper tube sheet during operation.

88. Pitting corrosion, also known as localized corrosion, occurs when small, deep pits form on a metal surface. The more concentrated the corrosion byproducts and medium at the bottom of the pit, the more severe the effect, potentially leading to perforation.

89. Crevice corrosion occurs when components with crevices or areas covered by deposits are exposed to corrosive media, leading to localized corrosion within the crevice. This can happen in locations such as riveted joints, bolted connections, and beneath surface deposits on metal.

90. Intergranular corrosion happens when metal materials in certain corrosive environments (such as NaOH) experience a significantly faster dissolution rate along grain boundaries compared to the grains themselves, resulting in selective localized corrosion along the grain boundaries.

+86 512 68781993

+86 512 68781993